Il 18 novembre 1928 la Celebrity Productions distribuisce Steamboat Willie, diretto da Walt Disney, il primo cartone animato a presentare una colonna sonora con musiche, effetti sonori e dialoghi (benché non intelligibili) completamente sincronizzata.

I primi due corti della serie Mickey Mouse, intitolati L’aereo impazzito e Topolino gaucho e proiettati in anteprima nel 1928, non erano riusciti a impressionare il pubblico e ad ottenere un distributore. L’enorme successo del primo lungometraggio sonoro Il cantante di jazz (1927) aveva però portato la maggior parte delle sale cinematografiche statunitensi a costruire un impianto audio, così Walt Disney decise di trarre profitto da questa nuova tendenza ed essere il primo ad offrire un cartone animato con sonoro completamente sincronizzato.

La produzione di Steamboat Willie ebbe luogo tra luglio e agosto del 1928, e l’animazione fu realizzata principalmente da Ub Iwerks. La paternità della colonna sonora del film a oggi non è del tutto chiara, essendo stata attribuita a Wilfred Jackson, Carl Stalling e Bert Lewis. Neil Sinyard afferma però che Jackson ricordò di aver insegnato ai suoi colleghi il principio del metronomo e di aver poi suonato Turkey in the Straw all’armonica per consentire a Disney di cogliere il ritmo dell’azione.

Inizialmente c’era però qualche dubbio tra gli animatori che un cartone animato sonoro potesse sembrare abbastanza credibile, quindi prima che fosse prodotta la colonna sonora, Disney organizzò una proiezione di prova del film alla presenza di mogli e fidanzate dei membri dello studio, con musica ed effetti sonori realizzati dal vivo dagli animatori. La risposta del pubblico fu estremamente positiva, e diede a Walt la fiducia per andare avanti e completare il film. Disse poi nel ricordare questa prima visione: “L’effetto sul nostro piccolo pubblico era nientemeno che elettrico. Risposero quasi istintivamente a questa unione di suono e movimento. Pensavo che mi stessero prendendo in giro. Così mi misero in mezzo al pubblico e fecero ripartire l’azione. Fu terribile, ma meraviglioso! Ed era qualcosa di nuovo!“. Iwerks disse: “Non sono mai stato così entusiasta in vita mia. Niente da allora lo ha mai eguagliato“.

Walt si recò a New York per assumere una società che producesse il sistema audio. Alla fine si stabilì sul sistema Cinephone di Pat Powers, creato da Powers utilizzando una versione aggiornata del sistema Phonofilm di Lee De Forest senza dare alcun credito De Forest, una decisione di cui in seguito si sarebbe pentito.

La musica nella colonna sonora finale venne eseguita dalla Green Brothers Novelty Band e diretta da Carl Edouarde. I fratelli Joe e Lew Green della band assistettero anche alla sincronizzazione della musica con il film. Il primo tentativo di sincronizzare la registrazione con il film fu un disastro. Disney dovette vendere la sua spider Moon per finanziare una seconda registrazione. Questa fu un successo grazie al filmato di una palla che rimbalza per mantenere il ritmo.

Steamboat Willie debuttò allo Universal’s Colony Theatre a New York il 18 novembre 1928. Il film venne distribuito dalla Celebrity Productions e la sua uscita iniziale durò due settimane. Disney venne pagato 500 dollari a settimana, che era considerata una grande quantità all’epoca.

Il successo di Steamboat Willie portò la fama internazionale non solo a Walt Disney, ma anche a Topolino. Il 21 novembre la rivista Variety pubblicò una recensione che diceva in parte: “Non è il primo cartone animato ad essere sincronizzato con effetti sonori, ma il primo ad attirare un’attenzione favorevole. [Steamboat Willie] rappresenta un alto ordine d’ingegno del cartone animato, sapientemente combinato con effetti sonori. L’unione ha portato a risate a bizzeffe. Le risatine sono arrivate così in fretta al Colony [Theater] che stavano inciampando l’una sull’altra“.

Nel 1994 il film si classificò al 13º posto nel libro The 50 Greatest Cartoons (I 50 Più Grandi Cartoni). Nell’aprile 1997 fu inserito (senza i titoli di testa e di coda) nel film di montaggio direct-to-video I capolavori di Topolino. Nel 1998 fu selezionato per la conservazione nel National Film Registry della Biblioteca del Congresso perché “culturalmente, storicamente o esteticamente significativo“.

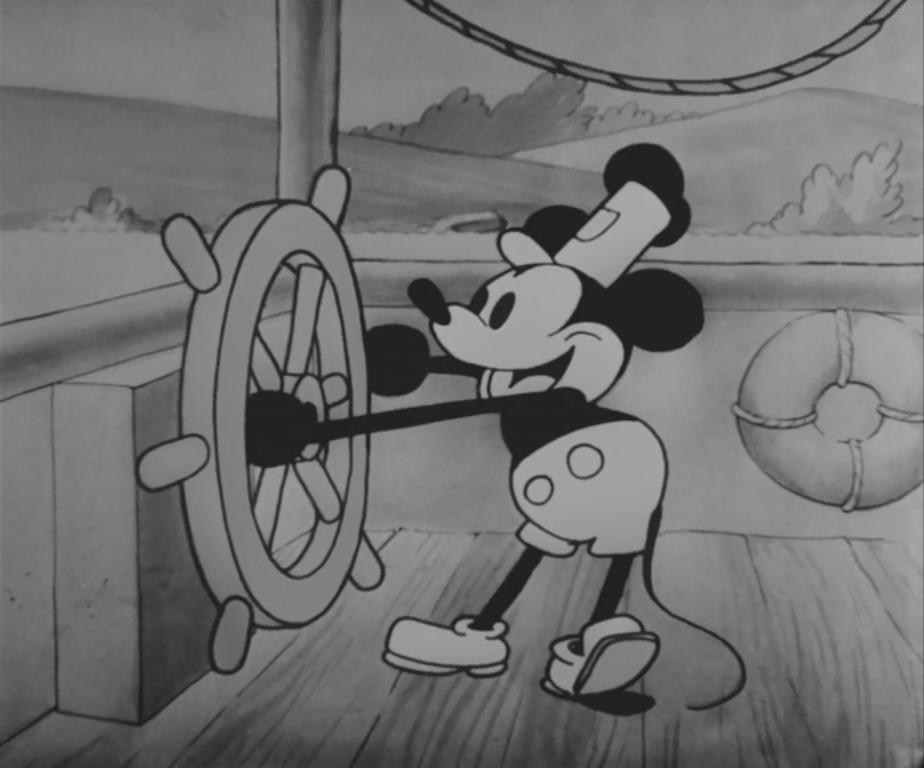

Immagine d’apertura: Topolino in una scena di Steamboat Willie

Bibliografia e fonti varie

- Bonus material commentary by Leonard Maltin, “Walt Disney Treasures: Mickey Mouse in Black and White”

- Walt Disney Treasures – Mickey Mouse in Black and White (1932) Archived January 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine at Amazon.com; the product description of this Disney-produced DVD set describes Steamboat Willie as Mickey’s debut

- Jump up to:a b Steamboat Willie (1929) Archived November 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine at Screen Savour

- Uytdewilligen, Ryan (2016). The 101 Most Influential Coming-of-age Movies. Algora Publishing. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-1-62894-194-4.

- The only spoken words are when Pete mutters “Get down there!” and several times the parrot says “Help! Man overboard!” and “Hope you don’t feel hurt, big boy!” – see here

- Beck, Jerry (1994). The 50 Greatest Cartoons: As Selected by 1,000 Animation Professionals. Turner Publishing. ISBN 978-1878685490.

- Jump up to:a b c Steamboat Willie at IMDb

- Salys, Rimgaila (2009). The Musical Comedy Films of Grigorii Aleksandrov. ISBN 9781841502823.

- New Scientist. June 7, 1979.

- The New Illustrated Treasury of Disney Songs. 1998. ISBN 9780793593651.

- Finch, Christopher (1995). The Art of Walt Disney from Mickey Mouse to the Magic Kingdom. New York: Harry N. Abrahms, Inc., Publishers. p. 23. ISBN 0-8109-2702-0.

- Korkis, Jim (2014). “More Secrets of Steamboat Willie”. In Apgar, Garry (ed.). The Mickey Mouse Reader. University Press of Mississippi. p. 333. ISBN 978-1628461039.

- Fanning, Jim (1994). Walt Disney. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 9780791023310.

- The Test Screening of Steamboat Willie

- https://www.loc.gov/programs/static/national-film-preservation-board/documents/steamboat_willie.pdf

- Jump up to:a b Steamboat Willie Archived March 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine at The Encyclopedia of Disney Animated Shorts

- Broadway Theater Broadway | The Shubert Organization Archived November 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine 1691 Broadway, between 52nd and 53rd Streets, now The Broadway Theater.

- “Talking Shorts”. Variety: 13. November 21, 1928. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- “Short Subjects”. The Film Daily: 9. November 25, 1928. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- Lawrence Lessig, Copyright’s First Amendment, 48 UCLA L. Rev. 1057, 1065 (2001)

- Lee, Timothy B. (January 1, 2019). “Mickey Mouse will be public domain soon—here’s what that means”. Ars Technica. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- ^ Lessig, Free Culture, p. 220

- ^ Jump up to:a b Menn, Joseph (August 22, 2008). “Disney’s rights to young Mickey Mouse may be wrong”. The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 21, 2009. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Vanpelt, Lauren (Spring 1999). “Mickey Mouse — A Truly Public Character”. Archived from the original on October 2, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Hedenkamp, Douglas A. (Spring 2003). “Free Mickey Mouse: Copyright Notice, Derivative Works, and the Copyright Act of 1909”. Virginia Sports & Entertainment Law Journal (2). Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Masnick, Mike (August 25, 2008). “Turns Out Disney Might Not Own The Copyright On Early Mickey Mouse Cartoons”. Techdirt. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

Disney warned him that publishing his research could be seen as “slander of title” suggesting that he was inviting a lawsuit. He still published and Disney did not sue, but it shows the level of hardball the company is willing to play.

- Mint, Perth (November 27, 2014). “DISNEY – STEAMBOAT WILLIE 2015 1 KILO GOLD PROOF COIN”. Pert Mint. Archived from the original on November 28, 2014. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- “Introducing LEGO® Ideas 21317 Steamboat Willie”. March 18, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- “Complete National Film Registry Listing | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board | Programs at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress”. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- “Hooray for Hollywood (December 1998) – Library of Congress Information Bulletin”. www.loc.gov. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- “Mickey Mouse in Black and White DVD Review”. DVD Dizzy. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- “The Adventures of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit DVD Review”. DVD Dizzy. Retrieved February 14, 2021.

- “The Best of Mickey Collection Blu-ray”. Blu-ray.com. Retrieved May 23, 2021.